Applying the Bradford Hill Criteria to Economics and Policy

Sir Austin Bradford Hill was an English epidemiologist and statistician, who after pursuing an economics degree at London University, became involved with studying the field of public health. He is most famous for pioneering the randomized clinical trial, but the focus of my blog post will be on his contribution that is less known outside of epidemiology and statistics: the Bradford Hill Criteria.

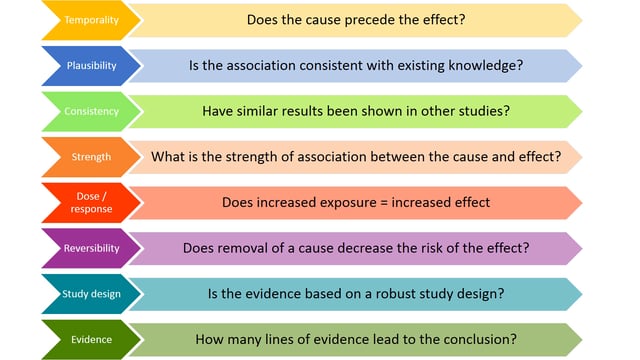

The Bradford Hill Criteria are a set of principles to establish the relationship between suspected causes and observed effects in the field of public health. In practice, he used this criteria in a long term study to demonstrate the effects of smoking on lung cancer.

These principles can be summarized in the following chart:

These criteria mostly talk about ways of demonstrating plausibility of causes, measuring its strength, its consistency, appealing to experimental data, corroborating evidence etc. And while there’s plenty of debate about the ways in which researchers apply these criteria to prove causal relationships, it really forms the basis of the way we sudy health.

I first heard about this in passing in some biology classes, as well as being discussed more thoroughly in the fantastic data science podcast Not So Standard Deviations. From there the concept really grabbed me, and since then I’ve been thinking about it on and off.

As a data scientist and coming from a science background, I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of testing theories/hypotheses. Using the scientific method we can move from idea to hypothesis to demonstration to observation to analysis. And from doing this time and time again, doing experiments, publishing research, having others read it, reproduce it, we further develop the various fields of science.

But the world of economic and policy research is very different.

Society is messy

Making sense of the real world is incredibly complicated because of how many variables that change people’s behaviors and responses. Trying to demonstrate that a policy or an economic principle actually works is incredibly difficult in a controlled experimental setting. Not to mention the costs of some of these experiments could be exceedingly prohibitive. For the most part in these fields we often use pre-existing data and apply regression analysis to do hypothesis testing.

And this isn’t to say experimentation isn’t being done in these fields. There has been fantastic work in the developing world experimenting the effects of micro-credit programs. A few studies can be found here and here.

But it seems to me that not enough is being done in this space.

Governments are too afraid of experimenting with policies and failing in the eyes of the public. Economics departments are comfortable doing traditional analysis because the process of publishing a paper becomes much easier and less resource/time consuming.

But we can do better

In public health, there’s an expectation that research be properly experimented and using specific criteria like Bradford Hill’s, we can establish with more rigor that there are causal relationships between causes and effects. I think this mostly stems from idea of lives being on the line when we’re talking about the ramifications of health research. People are more cautious, and are willing to spend the time and energy to do proper controlled experiments.

Although, when you think about it, the effects of policy and economics research can be just as important. This the fabric of our societal well-being that is on the line when we’re talking about possibly implementing basic income, or changing tax policies, or introducing new environmental controls.

I think these fields could really use some time to rethink the way we approach research.

Maybe we could take a hand out of Bradford Hill’s notebook and establish our own set of principles; a set of criteria that guides us through the process of evaluating a policy proposal. And furthermore, establishing more political and academic will to experiment (I also find academia and governments live in their own little bubbles without collaborating enough). The examples of microfinance are extremely pertinent, we know that this type of research can be effective. We just the need the will to change our mindset.

A set of principles

So with this whole discussion, I figured I’d take a stab at trying to apply this criteria to the world of policy:

These are just things I’ve been pondering. This is not by any means a definitive adaptation of the criteria to the world of policy/economics. I just have been thinking about this a lot and wanted to start that conversation.

As a Canadian, our civil service has done a much better job than most other countries but there’s always ways to improve. I think this is a huge area where the government can advance in. We just need to just need to take that first step.

Comments powered by Talkyard.